Understanding Montessori’s Educational Foundation

Dr. Maria Montessori’s research led her to a revolutionary conclusion: intelligence is not rare among human beings but manifests naturally through the spontaneous curiosity present in children from birth. She observed that when children grow up in intellectually and artistically alive environments—spaces that are warm and encouraging—they spontaneously ask questions, investigate, create, and explore new ideas. Children, especially in their early years, possess a remarkable capacity to absorb information, concepts, and skills from their surroundings and peers through what might be described as educational osmosis.

Montessori argued that learning can and should be a relaxed, comfortable, natural process. The key lies in understanding the hidden nature of the child at each developmental stage and designing environments—both at home and school—where children begin to fulfill their innate human potential.

As a school founder, you must understand that Montessori education extends far beyond teaching basic skills and information. While cultural literacy matters, children must also learn to trust their own ability to think and solve problems independently. Montessori encourages students to conduct their own research, analyze their findings, and reach their own conclusions. The goal is to cultivate independent thinkers who actively engage in the learning process.

Rather than providing students with correct answers, Montessori teachers ask the right questions and guide students to discover answers themselves. Learning becomes its own reward, with each success fueling the desire to learn even more.

Accommodating Individual Learning Differences

Montessori recognized that students learn in different ways and at different rates at every age level. Many children learn far more effectively through direct hands-on experience than from textbooks or lectures. However, all students respond to careful coaching with ample time to practice and apply new skills and knowledge. Like all of us, children learn through trial, error, and discovery.

Critically, Montessori students learn not to fear mistakes. They quickly discover that few things in life come easily, and they develop the confidence to try again without embarrassment. This resilience forms a cornerstone of lifelong learning.

The Spiral Curriculum: Integration Over Compartmentalization

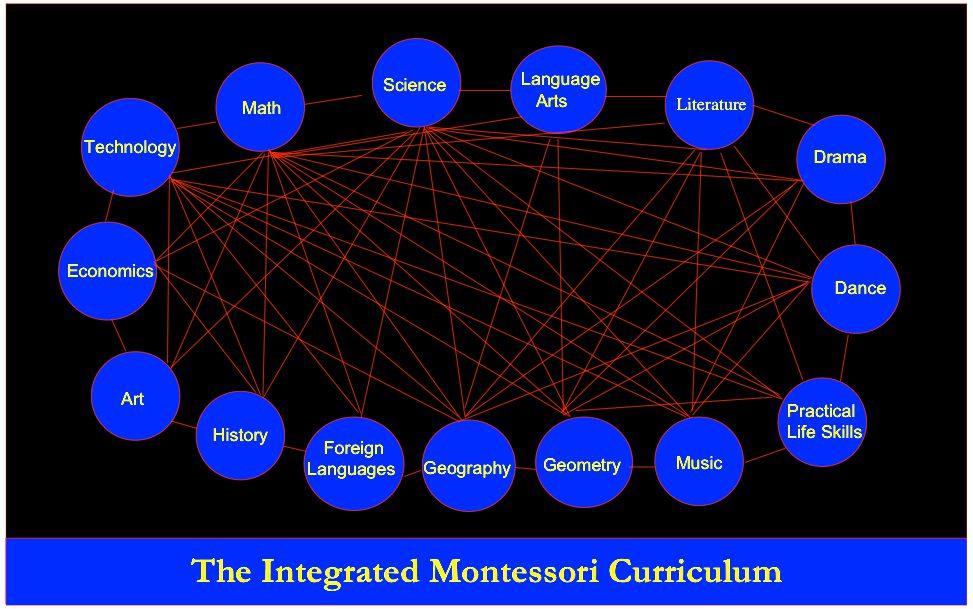

The Montessori curriculum is organized as an inclined spiral plane of integrated studies rather than the traditional model that compartmentalizes learning into separate subjects, with topics addressed only once at a given grade level. Lessons are introduced simply and concretely in the early years, then reintroduced multiple times over subsequent years with increasing abstraction and complexity.

The Montessori course of study employs an integrated thematic approach that connects disciplines into unified studies of the physical universe, the natural world, and human experience. Literature, the arts, history, social issues, civics, economics, science, and technology all complement one another seamlessly.

This integrated approach represents one of Montessori’s greatest strengths. Consider how elementary students might study Africa: they examine physical geography, climate, ecology, and natural resources, exploring how people have adapted to their environment through food, shelter, transportation, clothing, family life, and traditional cultures. They read African folktales, study great African civilizations, research endangered species, create African masks and traditional instruments, make African block-print t-shirts, learn Swahili phrases, study African dance in music classes, and prepare traditional meals from various African cultures. Guest speakers, performers, and community members help bring studies alive through their memories, talents, and personal experiences.

Practical Life: Independence and Community

Success in school directly correlates with the degree to which children believe they are capable and independent human beings. Even very young children essentially ask, “Help me learn to do it for myself!”

As we enable students to develop meaningful independence and self-discipline, we establish patterns for lifelong good work habits and responsibility. Montessori students are taught to take pride in their work.

Independence must be learned rather than simply emerging with age. In Montessori classrooms, even small children learn to tie their own shoes and pour their own milk. Initially, shoelaces become knotted, and milk spills on the floor. However, with practice, skills are mastered, and young children beam with pride. Experiencing success at an early age builds a self-image as capable, leading children to approach subsequent tasks with confidence.

As they mature, Montessori students master everyday living skills ranging from cleaning, cooking, and sewing to first aid and balancing checkbooks. They plan parties, learn to decorate rooms, arrange flowers, garden, and perform simple household repairs. The Montessori curriculum deliberately builds numerous opportunities for students to gain hands-on practical experience.

Learning to work and play together peacefully and caringly within a community may be the most critical life skill Montessori teaches. Everyday kindness and courtesy are vital practical-life competencies. Students come to understand and accept their responsibilities to others. They learn to handle new situations they will face as they become increasingly independent, developing clear values and a social conscience.

Montessori consciously teaches everyday ethics and interpersonal skills from the beginning. Even the youngest child receives treatment with dignity and respect. Montessori schools function as close-knit communities where people live and learn together in environments of warmth, safety, kindness, and mutual respect. Teachers become mentors and friends. Students learn to value the diverse backgrounds and interests of their classmates.

Parents play a vital role in fostering community within Montessori schools. Through their volunteer service and participation in social events and celebrations, students get to know their friends’ families and develop a sense of belonging to an extended community. A common goal is leading each student to explore, understand, and grow into full and active membership in the adult world.

Language Arts: Reading, Composition, and Literature

The process of learning to read should be as painless and straightforward as learning to speak. Montessori begins by placing the youngest students in multi-age classes where older students already read. All children want to “do what the big kids can do,” and when intriguing work that engages older students involves reading, it naturally motivates younger children.

Montessori teaches basic skills phonetically, encouraging children to compose their own stories using the movable alphabet. Reading skills develop so smoothly in Montessori that students often exhibit a sudden “explosion into reading,” leaving children and families beaming with pride.

Typically, children quickly jump from reading and writing single words to sentences and stories. At this point, a systematic study of the English language begins: vocabulary, spelling rules, and linguistics. We teach very young children—as young as first grade—the functions of grammar and sentence structure just as they first learn to put words together to express themselves. This timing allows them to master these vital skills during a developmental period when they find them delightful rather than burdensome. Before long, they learn to write naturally and well.

During elementary years, Montessori increasingly focuses on developing research and composition skills. Students write daily, learning to organize increasingly complex ideas and information into well-written stories, poems, reports, plays, and student publications.

Most importantly, the key to our language arts curriculum is the quality of material children read. Instead of insipid basal readers, even very young students encounter first-rate children’s books and fascinating works on science, history, geography, and the arts. In an increasing number of Montessori schools, students begin the Junior Great Books program in kindergarten, with literary studies continuing every year thereafter.

Mathematics: From Concrete to Abstract

Students who learn mathematics by rote often lack a fundamental understanding or the ability to apply their skills in everyday life. Learning is much easier when students work with concrete materials that graphically illustrate what happens in mathematical processes.

Montessori students use hands-on learning materials to make abstract concepts concrete. They can literally see and explore what is happening. This approach to teaching mathematics, grounded in Dr. Montessori’s research, provides a clear, logical strategy to help students understand and build sound foundations in mathematics and geometry.

Consider how Montessori presents basic concepts of the decimal system to young children. Units are represented by single one-centimeter beads, tens by a unit of ten beads strung together, hundreds by squares made of ten ten-bars, and thousands by cubes made of ten hundred-squares.

Using these concrete materials, even very young children can build and work with large numbers. “Please bring me three thousand, five hundred, six tens, and one unit.” Children thus internalize clear images of how mathematical processes work.

From this foundation, all mathematical operations—such as adding quantities in the thousands—become clear and concrete, allowing children to internalize a clear understanding of how processes work.

The Montessori math curriculum draws from the European tradition of “Unified Math,” which leading American educators have only recently embraced. Unified Math introduces elementary students to the fundamentals of algebra, geometry, logic, and statistics, alongside arithmetic. This integrated study spans years, weaving together subjects that traditional schools typically ignore until the secondary grades.

In measurement operations, geometry provides the framework for performing calculations. In operations involving numbers, algebra provides systems of more abstract symbols through which more complex relationships can be understood. Calculations of area and volume, squares and square roots, exemplify situations where algebra, arithmetic, and geometry all intersect. For Montessori students, arithmetic, algebra, and plane and solid geometry have never been arbitrarily separated. Four- and five-year-old Montessori children can name geometric forms most adults wouldn’t recognize.

Elementary Montessori students continue to gain hands-on experience by applying mathematics to wide-ranging projects, activities, and challenges—graphing daily temperatures and computing monthly averages, or adjusting recipe quantities for larger groups. Because children love outdoor work, teachers prepare tasks using the school grounds whenever possible. Using simple geometry, children determine tree heights or measure building dimensions. They prepare scale drawings, calculate area and volume, construct three-dimensional geometric models, and build scale models of historical devices and structures.

Computers are key tools for teaching mathematics. Students use them to memorize basic math facts and to engage in simulations and problem-solving, competing against computers or making reasonable predictions in engaging role-playing scenarios. Students work with spreadsheets, graphs, and logical analysis.

Montessori mathematics includes careful study of practical mathematical applications in everyday life—measurement, handling finances, making economic comparisons, gathering data, and conducting statistical analyses.

History and International Culture

We are all members of the human family. Our roots lie in the distant past, and history reflects our shared heritage. Without a strong sense of history, we cannot know who we are as individuals today. The goal is developing global perspectives, making the study of history and world cultures cornerstone elements of the Montessori curriculum.

With this goal in mind, Montessori teaches history and world cultures starting as early as age three. Youngest students work with specially designed maps and begin learning names of continents and countries. Physical geography begins in first grade with studies of Earth’s formation, emergence of oceans and atmosphere, and evolution of life. Students learn about rivers, lakes, deserts, mountain ranges, and natural resources.

Elementary students begin studying world cultures in greater depth: customs, housing, diet, government, industry, arts, history, and dress. They learn to treasure the richness of their own cultural heritage and those of their friends.

Elementary students study human emergence during old and new stone ages, development of first civilizations, and universal needs common to all humanity. For older elementary students, focus shifts respectively to early humans, ancient civilizations, and early American history.

Montessori strives to present living history at every level through direct hands-on experience. Students build models of ancient tools and structures, prepare manuscripts, make ceremonial masks, and recreate artifacts of everyday life from historical eras. Experiences like these make it far easier for Montessori children to appreciate history as taught through books.

International studies continue at every age level in Montessori education. The curriculum integrates art, music, dance, cooking, geography, literature, and science. Children learn to prepare and enjoy dishes from around the world. They learn traditional folksongs and dances in music and explore traditional folk crafts in art. In language arts, they read traditional folktales and research and prepare reports about countries they are studying. Units often culminate in marvelous international holidays and festivals that serve as school year highlights.

Practical economics forms another important curriculum element. Young students learn to use money and calculate change. Older students compute weekly meal costs for their class, plan weekly budgets, maintain checkbooks, organize and run holiday gift shops, sell produce they have grown, and create and sell cookbooks. Students learn to recognize the value of a dollar—how long it takes to earn and what it can buy.

Citizenship weaves throughout the elementary curriculum. Students study workings of local, state, and federal governments and begin following current events. During election years, they meet candidates, discuss current issues, and sometimes volunteer in campaigns for local candidates of their choice.

While Montessori schools are communities somewhat apart from the outside world—spaces where children first develop their unique talents—they are also consciously connected to local, national, and global communities. The goal is leading each student to explore, understand, and grow into full and active membership in the adult world.

Field trips often form integral parts of Montessori programs. Students take various trips over the years to planetariums, art galleries, zoos, museums, and many other destinations.

Foreign Languages

As part of international studies programs, most Montessori schools introduce second languages to even their youngest children. The primary goal in foreign language programs is developing conversational skills alongside deepening appreciation for the culture of the second language.

Science: Hands-On Discovery

Science is an integral curriculum element representing, among other things, a way of life—a clear-thinking approach to gathering information and solving problems.

The scope of Montessori elementary science curriculum includes sound introductions to botany, zoology, chemistry, physics, geology, and astronomy. The program is designed to cultivate students’ curiosity and determination to discover truth for themselves. They learn to observe patiently, analyze, and work through each problem. Students engage in field trips and hands-on experiments, typically responding enthusiastically to processes of careful measurement, data gathering, specimen classification, and hypothesis development to predict experiment outcomes.

Montessori does not separate science from the big picture of our world’s formation. Students consider universe formation, planet Earth’s development, delicate relations between living things and their physical environment, and balance within the web of life. These great lessons integrate astronomy, earth sciences, and biology with history and geography.

One goal of the Montessori approach to science is cultivating children’s fascination with the universe and helping them develop lifelong interests in observing nature and discovering more about the world they inhabit. Children are encouraged to observe, analyze, measure, classify, experiment, and predict—all with eager curiosity and wonder.

In Montessori, science lessons incorporate balanced hands-on approaches. With encouragement and solid foundations, even very young children are ready and eager to investigate their world, wonder at the interdependence of living things, and explore how the physical universe works and how it all may have come to be. For example, in many Montessori schools, children in early elementary grades explore basic atomic theory and processes by which heavier elements are fused from hydrogen in stars. Others study advanced biological concepts, including systems by which scientists classify plants and animals. Some elementary classes build scale models of the solar system stretching half a mile.

The Arts: Integration Across Subjects

In Montessori schools, the arts are normally integrated into the rest of the curriculum. They serve as modes of exploring and expanding lessons introduced in science, history, geography, language arts, and mathematics.

For example, students might make replicas of Grecian vases, study calligraphy and decorative writing, sculpt dinosaurs for science, create dioramas for history, construct geometric designs and solids for mathematics, and express their feelings about musical compositions through painting.

Art and music history and appreciation are woven throughout history and geography curricula. Traditional folk arts extend the curriculum as well. Students participate in singing, dance, and creative movement with teachers and music specialists. Plays and dramatizations make other times and cultures come alive.

Health, Wellness, and Physical Education

Montessori schools invest significantly in helping children develop control of their fine and gross motor movements. For young children, programs typically include dance, balance and coordination exercises, loosely structured cardiovascular exercise, and vigorous free play typical on any playground.

With elementary and older students, the ideal Montessori health, physical education, and athletics program differs markedly from traditional “gym” models. It challenges each student and adult in the school community to develop personal programs of lifelong exercise, recreation, and health management.

Many schools have limited space and facilities, but where funds and facilities are available for older students, the ideal Montessori gym offers variety in facilities and programs, potentially including rooms with stationary bikes and other child-appropriate exercise equipment, indoor tracks, basketball courts, rooms for aerobic dance, and perhaps even indoor pools and tennis courts. Ideally, these fitness centers would not be reserved for children alone—school families would be able to use facilities after hours, on weekends, and during school hours when it doesn’t interfere with student programs.

One important element in the Montessori approach to health and fitness is helping children understand and appreciate how our bodies work and the care and feeding of healthy human bodies. Students typically study diet and nutrition, hygiene, first aid, response to illness and injury, stress management, and peacefulness and mindfulness in daily lives.

Daily exercise is an important element of lifelong personal health programs, but instead of one program for all, students are typically helped to explore many different alternatives. Students commonly learn and practice daily stretching and exercises for balance and flexibility. Some programs introduce students to yoga, tai chi, chi gong, or aerobic dance. Children learn that cardiovascular exercise can come from vigorous walking, jogging, biking, rowing, aerobic dance, calisthenics, using stationary exercise equipment, actively playing field sports like soccer, or from wide ranges of other enjoyable activities such as swimming, golf, or tennis. With older students, the goal is exposing students to many different possibilities, encouraging them to develop basic everyday skills and helping them develop personal programs of daily exercise.

Implications for School Founders

As you establish your Montessori school, understand that the integrated curriculum represents not merely an educational philosophy but a comprehensive approach to human development. Your success depends on implementing this curriculum with fidelity while adapting to your specific community context.

Invest in comprehensive teacher training that ensures your staff understands not just individual curriculum areas but how they interconnect. Purchase authentic Montessori materials that support hands-on learning across all subject areas. Design your physical environment to accommodate the wide-ranging activities this curriculum requires—from science experiments to art projects to practical life activities.

Most importantly, resist pressures to compartmentalize learning in ways that appeal to parents familiar with traditional education models but undermine Montessori’s integrated approach. When you maintain curriculum integrity, the results speak for themselves: children who think independently, work collaboratively, and approach learning with genuine curiosity and confidence.