What are we (as Montessori educators and parents) to do with this new reality?

What will Montessori be in an ever-changing future?

We now live in an ever-changing future, and our Montessori goals are necessary preparations for children who need to learn how to adapt. We’ve been citizens in this kind of future for some time, and I suggest this one is different from other changing futures, such as the agricultural revolution or the industrial revolution. This one is different because its magnitude is all at once. It is continuous, and it is global. We are all affected; the sheer speed of this ever-change can be instantaneous. ‘Viral’ was once a feared proclamation of a deadly outbreak of disease. Today ‘going viral’ is a popularity contest based on a number of ‘thumbs ups’ and ‘likes.’

Montessori Students /Digital Natives

When I began teaching in the mid-seventies, children lined up waiting for their turn with the Geometric Cabinet. It was so popular that I used to think about getting a second one for my classroom. I never did, because that would have violated the one-material rule: Have one set of the material to cause sharing and respect. There were other very popular materials, too, that children waited for their turn, more or less patiently.

For some time now, I’ve noticed a different interest from children who are growing up as Digital Natives. There are children who are no longer drawn to many of our treasured didactic materials. Very few young children today are drawn to the Touch Tablets and more. This is a serious turn of events. The materials provide a concrete representation of an idea, and the idea is understood through tactile and other sensory exploration. According to Montessori theory, repeated use of the materials leads children to understand the embedded idea and grow cognitively. The use of the materials also leads children to develop concentration, persistence, and self-discipline. And it’s not just the children. We are also seeing a different interest from parents who grew up as Digital Natives. They were born in the digital world, and they know no other. Digital Natives are digital learners. Digital learners come with an expectation for “what is learning” that is different from our own. They use digital technologies incessantly. And this is transforming human relationships in fundamental ways.

Digital learners live much of their lives through their devices and without distinguishing between the online and the offline. Instead of thinking of their digital identity and their real identity as separate, they are just one identity with representations in two, or three, or more different spaces, real and virtual. We used to teach children not to hit anyone. Today a ‘hit’ and a ‘like’ are synonymous. Now it is good to ‘hit.’ Digital Natives learn software and shareware ‘instantly.’ They are endlessly and relentlessly creative. They construct and express themselves in new social environments. They take (online) courses to learn how to better position themselves in the digital marketplace.

Design usurps memorization as the fundamental learning activity. As stated by Google CEO, Eric Schmidt, in The New Digital Age, digital learners “perceive information as malleable; it is something they can control and reshape in new and interesting ways. That might mean editing a profile … or encyclopedia entries on Wikipedia, making a movie or online video, or downloading a hot music track … Whether or not they realize it, they have come to have a degree of control over their cultural environment that is unprecedented.”

There is also growing fear among digital learners. There is incredible access to uncensored information: access to hate information, cyber bullying, addiction to violent games, online predators, and more. Unsupervised and unsafe Internet usage can lead to identity theft and even abduction. We are tasked to educate children in safety. We are tasked to give children the tools and skills to keep themselves out of harm’s way.

I have long been a proponent of including technology in our prepared environments. I admit now that I am very worried—not just for the children—but for the future of our Montessori pedagogy. I used to say our Montessori materials engage a child with all of her senses, and this is optimal for full-brain development and learning. Now, the children and their parents, who come to our schools, bring different expectations, understandings, and aspirations.

Here is what we are seeing from the digital learners at our school:

- Many of our three-year-olds prefer working with others instead of choosing their own work or participating in parallel play. Why? Are they isolated from humans because at home and elsewhere they are using iPads or other digital devices? Is it because they are watching movies or TV on smart phones when immobilized in car seats or when they are at older siblings’ sports or other events?

- Many children want an initial presentation at the shelf. That is, they are not willing to carry all of the materials to a table or rug on the floor. They even comment that, on their tablets, they can see some of what the activity will be about before deciding to do it.

- A five-year-old declared he knew all about the 100 Board because he has that app on his tablet. When using the real 100 Board in the classroom, however, he could go no further than 30 because, he said, “The iPad always resets at the third row.” He had at home, in other words, the unpaid app version of the 100 Board.

- Another five-year-old knew the Addition Strip Board because, he said, “I do that on my iPad.” The classroom guide observed that when he used the real classroom version, he computed sums by counting on his fingers. When she asked him if he did the same thing with his iPad, he said, “No. I just punch the square, and if it’s wrong, it goes away.

Until recently, I was comfortable with technology as a supplement to our catalogue of materials; a supplement and not a replacement. But now, in our ever-changing future, certain technological advancements are occurring, and we will soon face a real ‘game changer.’ In the language of technological innovation, I fear that we are about to become disrupted.

The Evolution of Education

Our pedagogy is based on Dr. Maria Montessori’s discoveries of the child, beginning in the late 1890s and continuing through 1952. Montessori discovered that when children are placed in an environment designed for how they naturally learn, children will experience a transformation from impulsive behaviors. They will concentrate. And when children concentrate, they next develop self-reliance and become self-disciplined. For this to occur, the design of the environment, the design of the materials, and our own preparation must enable a child’s choice and spontaneous activity.

The whole of our pedagogy is rooted in touch, in the work of the hands. With the coordination of the hands comes independence and the child’s triumphant cry of, “I can do it!” With the coordination of the hands comes the development of intelligence. In her book, The Montessori Method, Montessori wrote:

I teach the child how to touch, that is, the manner in which he should touch surfaces. For this it is necessary to take the finger of the child and to draw it very, very lightly over the surface… Often, after the introduction of such exercises, it is a common thing to have a child come to you, and, closing his eyes, touch with great delicacy the palm of your hand or the cloth of your dress, especially any silken or velvet trimmings.

To touch is to learn. This occurs throughout the world and throughout time. The Sandpaper Letters, for example, are used by children to develop a cognitive understanding of the phonetic sounds of the alphabet. The child traces the letter and voices its sound. The child develops further literacy by associating objects with each letter and sound. The textures, colors, sizes, and weights of the objects are designed to attract and hold the child’s attention. This is true for all of the materials we place in our prepared environments. The materials call children to explore, investigate, concentrate, and make discoveries. The objects seem to express, “Do you want to know? Come find out.”

During the 20th century, our Montessori heritage stood in marked contrast to what we still call ‘traditional education.’ I can speak only for myself; perhaps you enjoyed your schooling. What I remember most was the agony of boredom, the fear of a teacher’s ridicule, the embarrassment of being wrong when called on, and the shame of being laughed at by others. Traditional education is rooted in a factory model of education. Teachers act like top-down managers and dispense information and assignments to children in predefined units and grades. We were told which book to take out, and for how long, and who would answer the first question, then the second, and then time was up. And, ready or not, interested or not, we moved on at the direction of the teacher/manager.

Throughout the education-as-manufacturing process, a ‘one size fits all’ controls the procedure. Instead of individualized instruction, children are interchangeable products. As children progress from grade to grade, they become more assembled. The teacher/manager measures success and failure in terms of grades and promotions. The teacher/manager is measured in turn by student test scores. A finished product occurs at graduation. The parallels between the school house and the factory are clear: teachers are managers; school assignments prepare children for work place tasks; grades will become salaries.

Memorization is the primary basis for learning. We memorized teacher-dispensed content, facts, dates, and formulas. We memorized the information and gave it back. We were scored for an accuracy of recall, and then we forgot about it. Many of us did fairly well; however, some of us fell within a tolerance of the education/manufacturing process known as one or more ‘standard deviations.’

In a traditional 21st century classroom, students are praised for their ability to find correct answers to predetermined questions. Intellectual risk taking, creative thinking, and asking questions is often discouraged. The ability to get a good score on a test is valued more than the ability to get fully engaged in the learning process and pursue ideas that excite a student. (www.wordpress.bhmschools.org/integration)

We memorized because it was assumed that what we needed to know was all that which our parents and our grandparents needed to know. Our future, when we grew up, would, resemble their own. We were raised in an ever-similar future.

Throughout the education-as-manufacturing process, a ‘one size fits all’ controls the procedure. Instead of individualized instruction, children are interchangeable products.

This kind of pedagogy stands in sharp contrast with our Montessori pedagogy. Our legacy is that of the prepared environment and developmentally appropriate, multi-sensory, hands-on learning activities. Montessori teachers are guides, who help children engage in investigation and discovery. Our goals include fully developing each child’s potential and forming habits of lifelong learning. Learning to think is not the same as learning to memorize. Developing habits of persistence, taking on challenges, engaging with problems, and creatively designing solutions are not the same as learning to memorize.

We now live in an ever-changing future, and our Montessori goals are necessary preparations for children who need to learn how to adapt. We’ve been citizens in this kind of future for some time, and I suggest this one is different from other changing futures, such as the agricultural revolution or the industrial revolution. This one is different because its magnitude is all at once. It is continuous, and it is global. We are all affected; the sheer speed of this ever-change can be instantaneous. ‘Viral’ was once a feared proclamation of a deadly outbreak of disease. Today ‘going viral’ is a popularity contest based on the number of ‘thumbs ups’ and ‘likes.’

Most telling, we are also the producers of this global change. Not feudal lords, dukes, and kings. Not mad men. Not industrial giants and manufacturing companies. Our everchanging future is driven by technological innovation and planned economic disruption. It is driven by a global participation in the consumption of digital devices and by the incessant 24/7/365 use of those devices. We each access more digital power than all other generations combined. Our access to knowledge and information multiplies daily. More and more of us text, and instant message, and take pictures, and make videos, and use FaceTime. We like, tweet, post, blog, open source, and do a whole host of verbs that didn’t exist just a few years ago. We’re all participants in producing constant change.

That we do all of this social media may yet prove to democratize our entire planet. And, if we are truly clever, we may yet even save ourselves from, at least, one other ‘everchanging future.’ This one is the ever-massive environmental destabilization, including the destruction of drinkable water. Say what you will about real reality and virtual reality. The ever-changing future is really real.

So, what is Montessori in this ever-changing future? Will children touch tablets? Will parents, who grew up as Digital Natives, identify with and understand our didactic materials? Will they want these for their children?

Certainly we have contended with technology in our prepared environment for some while now. I still recall personal computers in my middle school classrooms in the early 1980s. A ‘new generation’ of software appeared in the 1990s, offering Montessori-like computer based learning. More recently, there are Montessori apps, lots of them. I have felt for many years that our heritage was secure. And parents were in agreement. I would ask, “Do you prefer your child push—with their mouse or finger—an image of a pink cube, or carry real cubes?” I would ask, “Do you prefer less sensory stimulation from computer screens and tablets, compared with all senses engaged?”

These questions are about to become irrelevant because this digital world with these kinds of apps is about to go away. The kinds of digital learning about to become possible will require us to ask, what will Montessori be in an ever-changing future?

Teaching Thinking

Digital learners throughout the world are expressing changed expectations for how, what, where, and when to learn. It is no longer about does the app mimic a Montessori didactic material? In the 21st-century digital classroom, the profile of learning has changed. Digital learners do not memorize. They expect to learn how to think, create, analyze, evaluate, and more. This is not the factory model of schooling, and we are no longer the only non-factory game in town. Digital learners in non-Montessori schools routinely connect and collaborate with one another in real and virtual time and space. They explore, investigate, collaborate, solve problems, and communicate. They expect to become lifelong learners. Digital learners expect teachers to provide differentiated, personalized instruction. They expect hands-on learning experiences. They expect to explore real-world issues using models and simulations.

These words should sound familiar. We’ve used these words and their synonyms to describe and promote our legacy since 1907. Now, throughout the world, educators are determined: The factory model of traditional education will give way to teaching thinking. In digital classrooms, teachers are no longer a main source of information; text books are no longer a main source of information. Learning is no longer at the discretion of the teacher as factory manager. Given the omnipresent Internet, learning is whenever, wherever, and forever. Twenty-first century students collect and create information anywhere and anytime. They Bing, Google, Ask, Yahoo, Amazon, text message, blog, podcast, flip board, YouTube, mp3, mp4, RSA, Wiki, Facebook, FaceTime, crowdsource, and tweet. Twenty-first century students collect and create information when they publish and evaluate work using Ning, OneNote, Wiki, Picasa, Shutterfly, Photoshop. They collaborate with SkyDrive, Dropbox, Facebook, Skype, and Twitter.

The 21st century teacher is an information architect who guides students to validate information, problem solve, and communicate information Twenty-first century goals for students include developing a questioning disposition, embracing change, and thinking like entrepreneurs. Technology is not used to entertain. Using technology, a 21st century teacher can offer flexible learning paths— individualized instruction with open-ended, higher-order questions. Using technology, a 21st century teacher can evaluate authentic applications of learned knowledge and skills. (http://bionicteaching.com) The digital classroom is likely to be flipped—you take your lessons at home, and then work with your teacher/guide at school.

Twenty-first century homework engages students in collaborating, creating, publishing, and more. At any given moment, a learning experience might include:

- What are the effects of erosion on an average beach? How can we counteract this? Use any resource you wish.

- You have $1,000 to donate towards hunger relief. To which organization in which country would you give? How could you assess the impact of your donation?

- Make a model of one trillion.

- Read the terms and conditions of YouTube and summarize the key ideas.

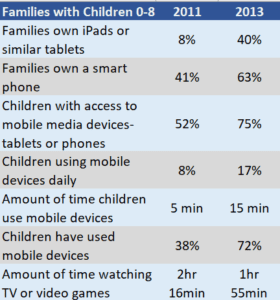

In an ever-changing future, children use technology to think and to make changes and design their future as engaged participants. They collaborate as authors, originators, inventors, creators. They are learning to plan, design, implement, and communicate. How will our didactic learning materials stand up to technology that enables simulations, modeling, systems thinking, and still more? We are oriented towards children developing coordination which, in turn, will enable them to concentrate, develop self-reliance, and become independent. Can we be so sure that these occur exclusively with only our didactic materials? Will parents, who are also Digital Natives, still choose Montessori? I cannot definitively answer this question. But these data are suggestive:

A year ago, we decided not to permit Minecraft during our afterschool programs. Several parents protested—not their children!—and they came back loaded with evidence of the educational whole-child benefits of Minecraft. Their sources included faculty at MIT and elsewhere. Minecraft is a thinking tool.

Children can plan entire cities, study environmental issues, and learn a programming language. Research on the benefits of Minecraft documents that children develop spatial reasoning, construction skills, and habits of learning how to learn.

Do Digital Devices Belong in the Montessori Prepared Environment?

Montessori educators have debated for several decades whether or not digital devices belong in the prepared environment. Some are adamant and proclaim no. Some ask what Dr. Montessori would do. Some are concerned that excessive use of digital devices erodes the child’s brain. And there is still more that is about to occur.

“Five years from now,” states an announcement from IBM, we will be able to understand touch and smell through our digital devices. IBM. (Touch: 5 future technology innovations from IBM) This to me is the real game changer. Touch and smell through our devices. Our brains will not differentiate real from virtual; our brains will not care. Already people wear sensing digital devices to frame a scene with their fingers and then take a picture. Other devices project images we see onto any surface. We continue, in other words, to learn through touch, but digitally. This is not the distant future; we should expect a new generation of digital classroom experiences rather soon.

There is no reason for us to think either/or—either our didactic materials or technological devices. Many of us do, instead, think both/and, both materials and devices. Each is a tool for learning, for communicating, for solving problems, and more. The Pink Cubes are a tool that offers a possibility not presented in other tools. A digital device offers a possibility for thinking not found in other tools.

There is, presumably, more to life than being logged into a digital device. I sincerely believe that in the ever-changing future there will be device-free learning moments. I sincerely believe that these moments are necessary complements and will perhaps even prove to make possible a whole-child education, with or without our Montessori devices. For example, since this past summer, outdoor construction has occupied most of our first through sixth graders during recess time. Their constructions have had various names and purposes. They began as office buildings. Then they became forts, but early in the fall, it was generally agreed that forts were not in keeping with our Montessori peace education purposes. So, their constructions were renamed as houses and shops. Well, renamed sort of. Last fall, a student paper came out from our E2 program with the headline, “Fort Crown: Split Up in the Big Fort.” The article went on to state, “Bill and Tom split up with the hotel. The hotel members are fine, happy, and they rebuilt very well. Bill and Tom also built their pawn shop there.”

These are essential opportunities in which children engage and participate. They collaborate as authors, originators, inventors, creators. They think, plan, design, implement, and communicate. I do agree with Richard Louv’s Last Child in the Woods:

Nature—the sublime, the harsh, and the beautiful—offers something that the street or gated community or computer game cannot. Nature presents the young with something so much greater than they are; it offers an environment where they can easily contemplate infinity and eternity. A child can, on a rare clear night, see the stars and perceive the infinite from a rooftop… Immersion in the natural environment cuts to the chase, exposes the young directly and immediately to the very elements from which humans evolved: earth, water, air, and other living kin, large and small. Without that experience … “we forget our place; we forget that larger fabric on which our lives depend.”

The Role of Montessori Educators and Parents in the Ever-Changing Future

What role will Montessori educators and parents play in an ever-changing future? I propose the establishment of a Montessori task force charged with establishing a 21st Century Montessori Pedagogy. I suggest we begin to:

- Develop 21st-century vision and purposes for schools;

- Evaluate developmental/brain studies;

- Define learning in the context of the ever-changing future;

- Identify principles for real and digitally prepared environments and learning materials and experiences;

- Research uses of digital and Montessori learning tools;

- Analyze the current catalog of Montessori materials;

- Propose Montessori digital learning tools; and

- Implement a Montessori digital teacher education.

Not either/or. How will we incorporate our Montessori heritage and legacy with emerging digital-based learning possibilities? How should we prepare environments when the distinction between real and virtual is collapsed? Which historic didactic materials should we maintain when digital devices will enable us to experience a full sensory array? What new materials do we need now? How will we design our Montessori ever-changing future?

TOMORROW’S CHILD © ♦ APRIL 2014 ♦ WWW.MONTESSORI.ORG