DECISION MAKING

The mantra “be fun to play with; be fun to play against” still works with upper elementary (9-12-year-olds), even though they are older and more mature. Their conflicts can be more complicated, and we need more than the mantra to solve some disagreements. A typical example is when one student criticizes another student who was distracted or not paying attention, causing a missed play or mistake. The criticizer wants them to pay attention and play better, which makes sense. A distracted teammate is not fun. However, the student being criticized usually does not like the criticism, and may not want to play anymore. The student criticizing a teammate is not being fun to play with either. Each point of view is valid, so how do we approach a topic like this?

Suppose the students cannot handle the disagreement in the moment and need a teacher mediator. In that case, I will ask a straightforward question to the student who is being portrayed as the aggressor.

“What was the intended outcome?”

Another way to ask this question is, “What did you want to happen?”

These questions get to the source of the conflict. The motivations and intentions of the students become apparent. We can have a logical conversation about the choices and consequences made, and emotions can be identified and expressed. Enhanced empathy allows both to reach a satisfactory compromise.

Let’s take a deeper look at the motivations of the criticizer. After I ask what they want to happen, they answer that they want the other student to pay attention.

Logically, this would probably improve the teammate’s performance, thereby improving the whole team’s performance. However, in this case, the criticism leads to the other player shutting down and not wanting to play anymore. They feel embarrassed and sad, so their performance suffers.

This is the opposite of what the criticizer wanted, but that is what commonly happens.

Additionally, the criticized student will have negative feelings toward their teammate, which may last far longer than that day.

This could lead to poor performance in the future or not wanting to play with this student at all (analyzing situations).

If we can help the criticizer understand the situation, we can help them to conclude that public criticism may not be the best course of action anymore.

It didn’t get the desired result; it worsened the situation. It hurt their teammate’s feelings, and hurt feelings take time to heal.

We can now explore alternate solutions with the criticizer, because we know criticism in this scenario didn’t work. We can ‘game plan’ with new solutions if this scenario happens again. For example, the student could privately remind the student to pay attention next time (goal setting).

BE FUN TO PLAY WITH; BE FUN TO PLAY AGAINST.

The student who wasn’t paying attention is not off the hook. We know that distracted teammates are not fun to play with, so we need to find out how (or why) they were distracted. Maybe it was a simple accident or mistake, so we know they will try harder next time, and it is as simple as that. Perhaps, they were talking to a friend and had been ignoring their responsibilities as a good teammate. Maybe this was not the first time this player has made a mistake in this game, and, they have made lots of errors due to an ongoing conversation with someone else. We need this context to analyze the situation truly.

There is a good chance that the criticizer did their best to manage their emotions, but after too many errors from the distracted player, they had had enough. It can be very frustrating when a teammate is not trying their best, especially when the other players put in maximum effort.

We expect everyone on our team to put forth the same effort we are, and when that expectation is not met, we can get upset. So, we need to remind the distracted player that to be a good teammate, they need to focus and put forth a good effort, which makes it fun to play with them.

We can only expect our teammates to do their best, knowing they will make mistakes. If the distracted student just made a simple mistake, we want to equip them with language that will help them acknowledge their mistake, and they will try harder next time.

This will build resilience and self-confidence because criticism in the future will be met with a plan of action, and they will not take it personally.

This communication with the teammate will prove they are actively listening and show that they are a good teammate.

With amped-up feelings and the game’s intensity, students are not ready to have this conversation immediately. We usually need time to have a mediation or peace talk.

However, if the behavior is not an isolated incident to those specific students, and it is something I am observing happening with several class members, I have no problem stopping the whole game and having this conversation with the entire class.

I need to fight my impulses to let things slide and continue the game to get maximum playing time at the expense of how the children are treating each other. We want the students to know that how they treat each other is as important as the game itself.

So, what do we do with our mature upper elementary and middle school students? Is there a way to promote sportsmanship past the definition they learned half a lifetime ago (be fun to play with, be fun to play against)? While it still applies, it’s simplistic, and we need something new to deal with the coming reality that they will be leaving the school soon.

They will be high schoolers, college students, and so on. They are at an age when they can truly perceive the future. We want them to be able to put things in perspective to guide their decisions. We must employ Social and Emotional Learning skills. For this age group, we have a new mantra: “Value the long term over the short term.”

From a strict sports perspective, we must strive for success in achieving the ultimate goal: a championship. We do this by creating smaller goals to achieve in practice and games, which serve to achieve the ultimate goal. For example, a team works on passing in practice sessions, which reduces turnovers in a game, and gives them a better chance of winning a championship because now they will turn the ball over less than their opponent.

Valuing the long term and the short term easily applies to life. The goal of each day is to make it better than yesterday in whatever you are trying to achieve. Continually achieving little goals accumulates into the achievement of a bigger goal. We want to achieve many big goals in our lifetime, but they happen through small incremental improvements.

What about luck? I have heard luck described as “when timing meets opportunity,” but there is an underlying fact that the person also needs to be capable. They made themselves capable through their work, whether they knew it or not. There was no way I could have predicted the combination of all the skills I would need to be where I am today. However, because I have those skills, through years of practice, I find myself in the position I am in, and I feel grateful for how things have turned out so far. When students ask, “Why do I have to learn this; I will never use it?” one of the answers is they might use it, but there is no way of us knowing for sure. As educators, we are trying to give them the potential for as many options as possible. There is no way we, or they, can predict how their life will unfold.

VALUE THE LONG TERM OVER THE SHORT TERM

Valuing the long term over the short term reminds me of a Swahili saying that my dad taught me. Before I get to that, if you are wondering, “Why does Nick’s dad know Swahili?” He was an associate professor of Swahili and African literature at Northwestern University

for over thirty years. I owe a lot of my analytic and critical thinking skills to his ability to let me ramble on and on as a child, and then he would ask key questions that forced me to reevaluate my position. My mother was a Montessori toddler teacher for over thirty years as well. The apple did not fall too far from the tree in that regard. Contrary to what many people assume about Montessori teachers of young children (they are all hippies), she showed me (and her students) a love of discipline. She also had intense powers of observation, and she consistently revealed character traits of a toddler that forecasted the adult they would become to their parents.

Let’s get back to the Swahili proverb. It is: haba na haba hujaza kibaba. The literal translation is, “little by little, the container gets filled.” This is a beautiful metaphor for how a long-term goal is accomplished.

When I talk to the students about valuing the long term over the short term in our Physical Education (PE) class, we talk about maintaining relationships (relationship skills). In PE, no one day or game is worth the cost of a friendship.

While winning a game is nice, that is not the goal. The point of physical education class is to learn through playing, practice sportsmanship, and get the exercise that facilitates gross and fine-motor movement patterns.

Some games have winners; others don’t, but winning is not, nor will it ever be the ultimate goal. Therefore, if someone values a game’s outcome more highly than a peer’s relationship, they are making a terrible mistake.

When we talk about valuing the long term over the short term regarding a team sport; maintaining relationships is still paramount, but the season’s outcome also bears some weight. It is possible to have a successful season and lose every game, but it takes a lot of subjective explanation to define the successes.

Winning a game, or especially winning a championship, is a more objective measure of the season’s success.

However, a winning season can be a failure if things were done to win a championship that ruins the players’ desire to continue playing in the future.

A coach can be successful on paper, but it can also be a failure of a coach on the human level if they break their players’ spirit and kill their motivation to play. Becoming the villain that your own team must overcome by banding together against you is a poor way to find success.

Winning a championship is the objective long-term success marker, and a game is a short-term goal.

Doing the little things in practice continues to add up, and our growth as players makes us more prepared for the game.

Playing game after game against different opponents teaches us more about ourselves than the opponent. It shows us what we must do to continue to get better, especially when the competition is close. As the team continues to improve, they put themselves in a better position to win a championship.

Not only do individual performances need to improve over the season, but also the team’s performance. Team performance is closely tied to how much trust the players have in each other and the coach.

Overly harsh words, resentment, envy, and other things that break trust erode the team’s fabric from the inside, and rarely does this team have long-term success.

An insult in practice bleeds over to the degraded performance in a game, and a lost game that was pivotal for the playoffs could be the difference in seeding for a championship run. Conversely, encouraging a player who failed in the moment shows that trust is still there, and that player feels secure that they can still contribute to the team in the future.

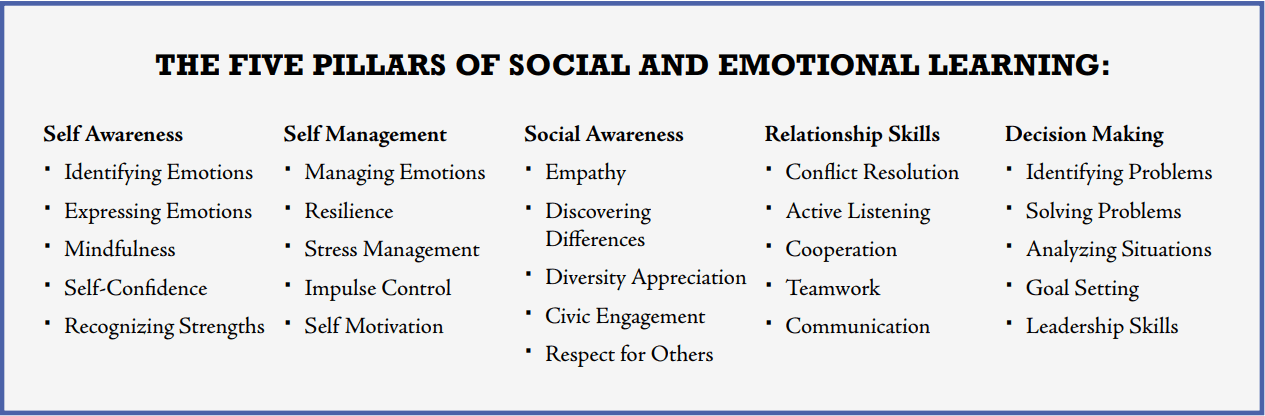

When we think of the Social and Emotional Learning toolbox, valuing the long term over the short term utilizes all the skills of decision making; identifying and solving problems; analyzing the situation; setting goals; and developing leadership skills. This is why team sports in school are held in such high esteem.

Whether adults realize it or not, the social and emotional skills that good team sports practice mimics how they will have to be used in real life.

As individuals, we are simultaneously the coach and the athlete of our own lives. We must strategize and make goals like a coach, and we must put those plans into action as players.

Another term that gets thrown around is “executive functioning,” which is something Montessori schools seem to be especially good at teaching. It is the ability to make plans and act on them.

We love sports because it is the idealized version of how life should be. Rules are fair, and they apply to everyone equally. The daily grind that produces results over time is a microcosm of what it takes to achieve greatness in life.

We celebrate those who are good at sports, but we especially value those who are also good at sportsmanship. Someone who is a good sport understands universal truths about being a good person. If sport is life, then sportsmanship is the way to live a good life. •

————————————————————————————-

Nicolas Lepine is the athletic director, physical education instructor, and sports coach for Rogers Park Montessori School in Chicago, IL. Before working as an athletic director and physical education teacher, he was in the Montessori upper elementary classroom for over a decade. He has a B.S.in exercise physiology from the University of Illinois and a Master’s in Montessori Education from St. Catherine’s University, where he completed his AMS Elementary One and Two certificates. This unique combination of skills allowed him to create Montessori Physical Education, which is a curriculum that integrates the Montessori classroom curriculum with physical education games. You can find his website at MontessoriPhysicalEducation.com, where you can learn more about how PE games can teach Montessori concepts, a free resources section, and links to the weekly blog and store.