Why do they call it a Children’s House?

In her research, Dr. Montessori noted specific characteristics associated with the children’s interests and abilities at each plane of development. She argued that a school carefully designed to meet the needs and interests of the child will work more effectively because it doesn’t fight human nature. Montessori taught teachers how to “follow the child” through careful observation, allowing students to reveal their strengths and weaknesses, interests and anxieties, and strategies that work best to facilitate the development of their human potential.

This focus on the “whole child” led Dr. Montessori to develop a very different sort of school from the traditional adult-centered classroom. To emphasize this difference, she named her first school the Casa dei Bambini—the Children’s House.

There is something profound in her choice of words, for the Montessori classroom is not the domain of the adults, but rather a carefully prepared environment designed to facilitate the development of the children’s independence and sense of personal empowerment.

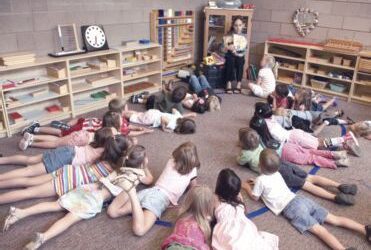

This is the children’s community. They move freely within it, selecting work that captures their interest. Even very small children assist with the care of the environment. When they are hungry, they prepare their own snacks. They go to the bathroom without assistance. When something spills, they help each other carefully clean up.

Generations of parents have been amazed to see small children in Montessori classrooms cut raw fruits and vegetables, sweep and dust, carry pitchers of water, and pour liquids with barely a drop spilled. The children normally go about their work so calmly and purposely that it is clear to even the casual observer that they are the ‘masters of the house.’

Montessori’s first Children’s House, which opened in 1907, was made up of sixty inner-city children. In her book, The Montessori Method, Dr. Montessori describes the transformation that took place during the first few months, as the children evolved into a ‘family.’ ey prepared and served the daily meals, washed the pots and dishes, helped the younger children bathe and change their clothes, swept, cleaned, and worked in the garden. These very young children developed a sense of maturity and connectedness that helped them realize a much higher level of their potential as human beings.

While times have changed, the need to feel connected is still as strong as ever. In fact, for today’s children, it is probably even more important. Montessori gives children the message that they belong—that their school is like a second family.

The Prepared Environment

Montessori classrooms tend to fascinate children and their parents. ey are normally bright, warm, and inviting, filled with plants, art, music, and books. ere are interest centers filled with intriguing learning materials, mathematical models, maps, charts, fossils, historical artifacts, computers, scientific apparatus, perhaps a small natural science museum, and animals that the children are raising.

Montessori classrooms are commonly referred to as a ‘prepared environment.’ is name reflects the care and attention that is given to creating a learning environment that will reinforce the children’s independence and intellectual development.

You would not expect to nd rows of desks in a Montessori classroom. The rooms are set up to facilitate student discussion and stimulate collaborative learning. One glance and it is clear that children feel comfortable and safe.

The Montessori classroom is organized into several curriculum areas, usually including language arts (reading, literature, grammar, creative writing, spelling, and handwriting); mathematics and geometry; everyday living skills; sensory-awareness exercises and puzzles; geography; history; science; art; music; and movement. Most rooms will include a classroom library.

Each area is made up of one or more shelf units, cabinets, and display tables with a wide variety of materials on display, ready for use as the children select them.

Students are typically found scattered around the classroom, working alone or with one or two others. ey tend to become so involved in their work that visitors are immediately struck by the peaceful atmosphere.

It may take a moment to spot the teachers within the environment. ey will normally be found working with one or two children at a time: advising, presenting a new lesson, or quietly observing the class at work.

Why do Montessori schools group children together in such large multi-age classes? A typical Montessori class is made up of 25 to 35 children, more or less evenly divided between boys and girls, covering a three-year age span. is practice has been a hallmark of the Montessori approach for almost one hundred years. Classes are guided by a certified Montessori educator, teaching with one or more assistants or by two Montessori teachers. In some situations, a class may be led by someone who is still in the process of completing the extensive Montessori teacher education process. On completion, teachers receive their Montessori certification.

Classes tend to be stable communities, with only the oldest third moving on to the next level each year. With two-thirds of the children returning each fall, Montessori encourages a much closer relationship among children and their peers, as well as among children and their teachers.

The levels usually found in a Montessori school correspond to the developmental stages of childhood: infant (birth through 18 months); toddlers (18 months to age 3); early childhood (age 3 to 6); lower elementary (age 6 to 8); upper elementary (age 9 to 11); middle school (age 12 to 14); and secondary/high school (age 15 to 18).

At each level, the program and curriculum are logical and highly consistent extensions of what has come before.

Many non-Montessori preschools are proud of their very small group sizes, and parents often wonder why Montessori classes are so much larger. Schools that place children together into small groups assume that the teacher is the source of instruction; a very limited resource even in a small class.

These schools reason that as the number of children decreases, the time that teachers have to spend with each child increases. Ideally, they would have a one-on-one tutorial situation.

But the best ‘teacher’ of a three-year-old is often another child who is just a little bit older and has mastered a skill. is process is good for both the tutor and the younger child. In the Montessori approach, the teacher is not the primary focus.

Montessori encourages children to learn from each other. By having enough children in each age group, all students will nd others at, above, and below their present level of development. is also makes Montessori schools economically more viable, allowing schools to attract teachers with far greater training and experience.

Some parents worry that by having younger children in the same class as older ones, one age group or the other will be shortchanged. They fear that the younger children will absorb the teachers’ time and attention, or that the importance of covering the kindergarten curriculum for the five-year-olds will prevent them from giving the three- and four-year-olds the emotional support and stimulation that they need. Experience has shown that both concerns are misguided and Montessori guides can’t imagine teaching in any other way.

MONTESSORI ENCOURAGES CHILDREN TO LEARN FROM EACH OTHER. BY HAVING ENOUGH CHILDREN IN EACH AGE GROUP, ALL STUDENTS WILL FIND OTHERS AT, ABOVE, AND BELOW THEIR PRESENT LEVEL OF DEVELOPMENT.

There Are Several Distinct Advantages to the Montessori Classroom Model

In a well-run established Montessori class, children are typically far more independent and self-disciplined. One factor that makes this possible is that each class ideally retains two-thirds of its class as the new term begins.

Each child has her own learning style. Montessori teachers treat children as individuals and customize lessons to t their needs, personality, and interests.

Since Montessori allows children to progress through the curriculum at their own pace, there is no academic reason to group children according to one grade level. In a mixed-class, children can always nd peers who are working at their current level.

Working in one class for two or three years allows students to develop a strong sense of community with their classmates and teachers. The age range also allows the especially gifted children the stimulation of intellectual peers, without requiring that they skip a grade and feel emotionally out of place.

To accommodate the needs of individual learners, Montessori classrooms have to include curriculum to cover the entire span of interests and abilities all the way through the oldest and most accelerated students in the class. This creates a highly enriched learning environment.

In these multi-level classrooms, younger children are constantly stimulated by the interesting work in which the older ones are engaged.

At the same time, in multi-level classrooms, older students serve as tutors and role models for the younger ones, which helps them in their own mastery (we learn things best of all when we teach to someone else) and leaves them beaming with pride.

Those Mysterious Montessori Materials:

The Road from Concrete to Abstract Thinking All children and most adults learn best through direct experience and the process of investigation and discovery. Most students do not retain or truly grasp much of what they ‘learn’ through memorization.

Asking a child to sit back and watch a teacher perform a process or experiment is like asking one-year-olds not to put everything into their mouths. Children need to manipulate and explore everything that catches their interest. Anyone who has lived with children knows that this is true.

It’s ironic that most schools today still teach primarily through lectures, textbooks, and workbooks. Most students still spend their days sitting behind a desk praying for the recess bell to ring.

Dr. Montessori recognized that concrete learning apparatus makes learning much more rewarding. e Montessori learning materials are not the Method itself; they are simply tools that we use to stimulate the child into logical thought and discovery.

An important concept is that for each age level of the Montessori curriculum, there is an extensive collection of carefully defined educational materials that are the equivalent of the chapters in a traditional textbook. Each material isolates and teaches one concept or skill at a time. In developing the materials, Dr. Montessori carefully analyzed the skills and concepts involved in each subject and noted the sequence in which children most easily master them.

She then studied how children seemed to be able to most easily grasp abstract concepts and designed each element to bring the abstract into a clear and concrete form.

The materials are displayed on low, open shelves that are easily accessible to even the youngest children. They are arranged to provide maximum eye appeal without clutter. Each has a specific place on the shelves, arranged from the upper left-hand corner in sequence to the lower right, following their sequence in the curriculum.

The materials are arranged in sequence from the most simple to the most complex and from the most concrete to those that are the most abstract. Because of the order in which they are arranged in the environment, children can nd precisely what they need whenever they wish.

Each of the Montessori materials is designed to allow children to work independently, with only the slightest level of introduction and ongoing support from the teachers. This is made possible by a built-in design element, the ‘Control of Error,’ which allows students to determine for themselves if they have done each exercise correctly. The materials can be used repeatedly at different developmental levels.

Each material has multiple levels of challenge. Lessons are brief introductions, after which the children repeat the exercise over many days, weeks, or months until they attain mastery. Interest leads them to explore variations and extensions inherent within the design of the materials at many levels over the years.

For example, the Trinomial Cube, which presents a complex and challenging three-dimensional puzzle to the five-year-old, is used to introduce the elementary child to the algebraic concept of the exponential powers of polynomials.

The Montessori Curriculum Montessori offers a rigorous and innovative academic program.

The curriculum is organized into a spiral of integrated studies, rather than a traditional model in which the curriculum is compartmentalized into separate subjects, with given topics considered only once at a specific grade level.

In the early years, lessons are introduced simply and concretely and are reintroduced several times over succeeding years at increasing degrees of abstraction and complexity.

The course of study uses an integrated thematic approach that ties the separate disciplines of the curriculum together into studies of the physical universe, the world of nature, and the human experience.

Literature, the arts, history, social issues, political science, economics, science, and the study of technology all complement one another. is integrated approach is one of Montessori’s great strengths.

As an example, when students study ancient Greece, they also study Greek mythology, read stories and novels set in the Grecian world, create authentic costumes, build models of Greek buildings, and explore Grecian art. They study the climate, ecosystems, flora, fauna, and natural resources of the world of the ancient Greeks. And they prepare plays, celebrate festivals, and re-stage their own version of historical events.

A Typical Day

In Montessori, the school day is not divided into fixed-time periods for each subject. Teachers call students together as they are ready, for lessons individually or in small groups.

A typical day’s work is divided into ‘fundamentals’ that have been assigned by the faculty, and self-initiated projects and research selected by the student. Students work to complete their assignments at their own pace. Teachers closely monitor their students’ progress, keeping the level of challenge high. Teacher feedback to students and parents helps students learn how to pace themselves and take a great deal of personal responsibility for their studies—skills that are essential for later success in college and in life.

We encourage students to work together collaboratively, and many assignments can only be accomplished through teamwork. Students constantly share their interests and discoveries with each other. e youngest experience the daily stimulation of their older friends and are naturally spurred on to be able to “do what the big kids can do.”

How can Montessori teachers meet the needs of so many di erent children? Montessori teachers do more than present curriculum. e secret of any great teacher is helping learners get to the point that their minds and hearts are open and they are ready to learn, where the motivation is not focused on getting good grades but, instead, involves a basic love of learning.

As parents know their own children’s learning styles and temperaments, teachers, too, develop this sense of each child’s uniqueness by developing a relationship over a period of years with children and their parents. Dr. Montessori believed that teachers should focus on children as indivduals, not on the daily lesson plan. Montessori nurtures the human potential, leading children to ask questions, think for themselves, explore, investigate, and discover. Our ultimate objective is to help them to learn independently, retaining the curiosity, creativity, and intelligence with which they were born.

Traditional teachers tell us that they “teach students the basic facts and skills that they will need to succeed in the world.” Studies show that in many classrooms, as much as 40 percent of the day may be spent on discipline, test preparation, and classroom management. Montessori educators play a very different role.

Wanting to underscore the very di erent role played by adults in her schools, Dr. Montessori used the title directress instead of teacher. In Italian, the word implies the role of the coordinator or administrator of an o ce or factory. Today, many Montessori schools prefer to call their teachers guides. Whatever they’re called, Montessori teachers are rarely the center of attention, for this is not their class; it is the Children’s House.

Normally, Montessori teachers will not spend much time working with the whole class at once. eir primary role is to prepare and maintain the physical, intellectual, and social/emotional environment within which the children will work. Certainly, a key aspect of this is the selection of intriguing and developmentally appropriate opportunities for learning to meet the needs and interests of each child in the class.

Montessori Guides Have Five Basic Goals:

• to awaken children’s spirit and imagination;

• to encourage children’s normal desire for independence and high sense of self-esteem;

• to help children develop the kindness, courtesy, and self-discipline that will allow them to become full members of society;

• to help children learn how to observe, question, and explore ideas independently; and

• to create a spirit of joyful learning, helping children master the skills and knowledge of their society.

Montessori guides rarely present a lesson to more than a handful of children at one time, and they limit lessons to brief efficient presentations. The goal is to give the children just enough to capture their attention and spark their interest, intriguing them so that they will come back on their own to work with the materials.

Montessori guides closely monitor their students’ progress, keeping the level of challenge high. Because they normally work with children for three years, guides get to know their students’ strengths and challenges, interests, and anxieties extremely well. Montessori guides often use the children’s interests to enrich the curriculum and provide alternate avenues for accomplishment and success.

Montessori Teaches Children to Think and Discover for Themselves

Montessori schools are designed to help children discover and develop their talents and possibilities.

While learning the right answers may get children through school, learning how to become lifelong, independent learners will take them anywhere! Montessori teaches children to think, not simply to memorize, pass a test, and forget.

Rather than present students with the right answers, Montessori educators tend to ask the right questions and challenge them to discover the answers for themselves. Older students are encouraged to do their own research, analyze what they have found, and come to their own conclusions.

Respect and Independence:

The Foundation of the Montessori Approach Montessori does not believe that intelligence is fixed at birth, nor is the human potential anywhere near as limited, as it sometimes seems in traditional education. These beliefs have been confirmed by the research of Jean Piaget, Howard Gardner, Angela Duckworth and many others.

We know that each child is a full and complete individual in her own right. Even when they are very small, children deserve to be treated with the full and sincere respect that we would extend to their parents. Respect breeds respect and creates an atmosphere within which learning is tremendously facilitated.

Success in school is directly tied to the degree to which children believe that they are capable and independent human beings. If they knew the words, even very young children would ask: Help me learn to do it for myself!

By allowing children to develop a meaningful degree of independence and self-discipline, Montessori sets a pattern for a lifetime of good work habits and a sense of responsibility. Students are taught to take pride in doing things well.

Freedom of Movement and Independently Chosen Work

Children touch and manipulate everything in their environment. In a very real sense, the adult mind is ‘hand made,’ because it is through movement, exploration, and manipulation that children build up a storehouse of impressions about the physical world. Children learn by doing, and this requires movement and spontaneous investigation.

Montessori children are free to move about, working alone or with others at will. ey may select any activity and work with it as long as they wish, so long as they do not disturb anyone, damage anything, and put it back where it belongs when they are finished.

Many exercises, especially at the early childhood level, are designed to draw their attention to the sensory properties of objects within the environment: size, shape, color, texture, weight, smell, sound, etc. Gradually, children learn to pay attention, seeing more clearly small details in the things around them. They begin to observe and appreciate their environment, which is key in helping them discover how to learn.

Freedom is a critical issue as children begin their journey of discovery. Our goal is less to teach them facts and concepts, but rather to help them fall in love with the process of focusing their complete attention on something and solving its riddle with enthusiasm.

Work that has been assigned by adults rarely leads to such enthusiasm and interest as does work that children freely choose for themselves. The Montessori classroom is a learning laboratory in which children are allowed to explore, discover, and select their own work.

Children become comfortable and con dent in their ability to master the environment, ask questions, puzzle out the answer, and learn without the constant intervention of an adult.

What is the most important thing that children get from Montessori?

The Montessori approach is often described as an “education for life.” When we try to define what children take away from their years in Montessori, we need to expand our vision to include more than just basic academic skills.

Normally, Americans think of a school as a place where one generation passes down basic skills and culture to the next. From this perspective, a school only exists to cover a curriculum not to develop character and self-esteem.

In all too many traditional and highly competitive schools, students memorize facts and concepts with little understanding, only to quickly forget them when exams are over. Studies show that many bright students are passive learners. ey coast through school, earning high grades, but rarely push themselves to read material that hasn’t been assigned, ask probing questions, challenge their teacher’s opinions, or think for themselves. They typically want teachers to hand them the ‘right’ answer.

The problem isn’t with today’s children, but with today’s schools. Children are as gifted, curious, and creative as they ever were when they’re working on something that captures their interest and that they have voluntarily chosen to explore.

Montessori schools work to develop culturally literate children and nurture their fragile sparks of curiosity, creativity, and intelligence. ey have a very di erent set of priorities than traditional schools and a very low regard for mindless memorization and super cial learning.

Montessori students may not memorize as many facts, but they do tend to become self-con dent, independent thinkers who learn because they are interested in the world and enthusiastic about life—not simply to get a good grade.

Montessori believed that there was more to life than simply the pursuit of wealth and power. To her, finding one’s place in the world, work that is meaningful and fulfilling, and developing the inner peace and depth of soul that allows us to love are the most important goals in life.

Helen Keller, inspired by Montessori, wrote:

“I believe that every child has hidden away somewhere in his being noble capacities which may be quickened and developed if we go about it in the right way, but we shall never properly develop the higher nature of our little ones while we continue to fill their minds with the so-called basics. Mathematics will never make them loving, nor will accurate knowledge of the size and shape of the world help them to appreciate its beauties. Let us lead them during the first years to nd their greatest pleasure in nature. Let them run in the fields, learn about animals, and observe real things. Children will educate themselves under the right conditions. They require guidance and sympathy far more than instruction.”

Montessori schools give children the sense of belonging to a family and help them learn how to live with other human beings.

To reduce these principles to the most simplistic form, Dr. Montessori proposed that we could make peace by healing the wounds of the human heart and by producing children who are independent, at peace with themselves, and secure. Dr. Montessori envisioned her movement as essentially leading to a reconstruction of society.

Montessori schools are different, but it isn’t just because of the materials that are used in the classrooms. Look beyond the Pink Towers and Golden Beads, and you’ll discover that the classroom is a place where children really want to be—because it feels a lot like home.

Help … Our Montessori school wants to ‘normalize’ our child!

Normalization is a term that causes a great deal of confusion and some concern among many new Montessori parents.

Normalization is a terrible choice of words. It suggests that we are going to help children who are not normal to become ‘normal.’ is is not what Dr. Montessori meant. Normalization is Montessori’s name for the process that takes place in Montessori classrooms around the world, through which young children learn to focus their intelligence, concentrate their energies for long periods, and take tremendous satisfaction from their work. One mother put it this way: “My child just does not act the same now that he’s been in Montessori awhile. He usually runs from one thing to another. In Montessori, he looks interested, sometimes puzzled, and often completely absorbed. I think of normalization as a kind of satisfaction that he seems to take from what he calls hard work.”

In his book, Maria Montessori: Her Life and Work, E.M. Standing described the following characteristics of normalization in the child between the age of three and six: • A love of order • A love of work • Profound spontaneous concentration • Attachment to reality • Love of silence and of working alone • Sublimation of the possessive instinct • Obedience • Independence and initiative • Spontaneous self-discipline • Joy • The power to act from real choice and not just from idle curiosity

Kay Futrell in her book, The Normalized Child, describes Dr. Montessori’s amazement when the sixty frightened and ill-disciplined inner-city children of her first Children’s House began to respond to the new environment. Normalization is another word for what we call Montessori’s Joyful Scholars.

What outcomes can we look for if we give our child a Montessori education? There are eight primary aspects to what we look for in children who have grown up with a Montessori education:

1. ACADEMIC PREPARATION: Montessori prepares students both for higher education and life. On an academic level, Montessori helps students attain skills that allow them to become independently functioning adults and lifelong learners.

2. INTRINSIC MOTIVATION: Innate desire drives Montessori children to engage in activities for enjoyment and satisfaction.

3. INTERNALIZED GROUND RULES AND THE ABILITY TO WORK WITHOUT EXTERNAL AUTHORITY: Montessori students are comfortable with ground rules that set the boundaries for their interactions within the school community. Because these ground rules become internalized, Montessori students normally learn to behave appropriately, whether or not teachers are present.

4. SOCIAL RESPONSIBILITY: Montessori children tend to be quite sensitive to the rights and needs of others. ey tend to make a positive contribution to their community.

5. AUTONOMY: Montessori students tend to become self-directed, composed, and morally independent.

6. CONFIDENCE AND COMPETENCE: Montessori students tend to become con dent, competent, self-reflective, and, thereby, successful. ey are generally not afraid of failure and learn from mistakes.

7. CREATIVITY AND ORIGINALITY OF THOUGHT: Montessori students become con dent in expressing their own ideas and creativity. ey recognize the value of their own work, respect the creative process of others, and are willing to share their ideas, regardless of the risk of rejection. Montessori students tend to take great satisfaction in self-expression.

8. SPIRITUAL AWARENESS: Montessori students are often exceptionally compassionate, empathetic, and sensitive to the natural world and the human condition. Will my child be able to adjust to traditional school after Montessori? Montessori children, by the end of age five, are normally curious self-confident learners who look forward to going to school. They are engaged, and enthusiastic. What teacher wouldn’t want a room filled with children like that? Well, truthfully, over the years we’ve found some who consider these children ‘disruptive.’

Disruptive? A polite, independent Montessori child, disruptive? Well, first off, let’s remember that Montessori children are real human beings, and not all children who attend Montessori schools fit the idealized description. However, enough do that the generalization is often accurate.

Montessori children, by age six, have spent three or four years in a school where they were treated with honesty and respect. While there were clear expectations and ground rules, within that framework, their opinions and questions were taken quite seriously. Unfortunately, there are still some teachers and schools where children who ask questions are seen as challenging authority.

You can imagine an independent Montessori child asking his new teacher, “But why do I have to ask each time I need to use the bathroom?” or, “Why do I have to stop my work right now?” We also have to remember that children are different. One child may be very sensitive or have somewhat special needs that might not be met well in a teacher-centered traditional classroom. Other children can go anywhere. In general, there is nothing inherent in Montessori that causes children to have a hard time if they are transferred to traditional schools. Some will be bored. Others may not understand why everyone in the class has to do the same thing at the same time. But most figure the new setting out fairly quickly, make new friends, and succeed within the definition of success understood in their new schools.

Naturally, there are trade-offs. The curriculum in Montessori schools is often much more enriched and accelerated than many found in other nursery and elementary schools in the United States. The values and attitudes of the children and teachers may also be quite different. Learning will often be focused more on adult-assigned tasks done more by rote than with enthusiasm and understanding.

There is an old saying that if something is working, don’t try to fix it. This leads many families to continue their children in Montessori at least through the sixth grade. As more Montessori high schools are opened in the United States and elsewhere around the world, it is likely that this trend will continue.

But other families, for financial or other reasons, don’t plan to have their children continue in Montessori. They often ask if there is any particular age level at which Montessori children tend to nd the transition particularly difficult? Because of individual differences in children and the next schools that are available to them, there is no absolute answer. In general, we strongly recommend that parents plan to keep their children in Montessori at least through the end of kindergarten.

MONTESSORI STUDENTS PERCEIVE THEMSELVES AS SUCCESSFUL PEOPLE BUT ARE NOT AFRAID OF MAKING AND LEARNING FROM THEIR MISTAKES.

Ideally, families should consider a commitment through at least elementary school; although, we can make a strong case that it is during the difficult middle-school years that children most need what Montessori has to offer. The development of successful Montessori high school programs means that more and more students have the opportunity to discover how well prepared they were for college and later life by their Montessori education.

Does Montessori prepare children for the real world?

In a word, yes! Here’s why. Montessori helps children master the intellectual skills and knowledge that are basic to our culture and technology.

As Montessori students master one level of academic skills, they are able to apply themselves to increasingly challenging work across the academic disciplines. ey tend to be re ective learners. ey write, speak, and think clearly and thoughtfully. ey have learned how to learn by doing real things in the real world—experiential learning. ey have learned how to integrate new concepts, analyze data, and think critically.

Children who grow up in Montessori schools tend to be culturally literate, well educated, and highly successful in university and later life. Today, these skills are commonly known as high-executive function.

Montessori develops intrinsic motivation: the innate desire that drives students to engage in an activity for enjoyment and satisfaction. Montessori cultivates creativity and originality: Montessori students are normally exceptionally creative in their thinking and con dent in self-expression. They recognize the value of their own ideas, respect the creative process of others, and are willing to explore ideas together in search of truth or new solutions.

Montessori students tend to be extraordinarily self-confident and competent. They perceive themselves as successful people but are not afraid of making and learning from their mistakes.

Montessori students do not see themselves as children, but as young members of the world. They tend to look up to teachers and other adults as mentors, friends, and guides, rather than as unwelcome taskmasters who place limits on their freedom.

Children who grow up in Montessori rarely feel the need to rebel and act out. Although even Montessori children will test their parents’ resolve, they basically follow an inner creed of self-respect. They accept limits, tend to follow common sense, and reach out to their friends and the larger community, seeking ways to help others and make a positive contribution to the world.

Montessori children are not easily in uenced by their peers. Like all of us, children who grow up in Montessori schools want to have friends, and are a ected by their interests and attitudes. On the other hand, in addition to having grown up in a culture that consistently teaches and follows universal values of kindness, honor, and respect, Montessori children tend to think for themselves.

Most Montessori students are exceptionally compassionate, empathetic, and sensitive to the natural world and the human condition.

Montessori children tend to have all the values and attitudes that pay off in college and the real world. ey aren’t afraid of hard work. ey are eager to learn, think, and explore new ideas. They enjoy people and develop strong friendships. They live from a basic sense of self-respect and rarely get themselves into self-destructive situations. ey tend to be self-disciplined, fairly well organized., and tend to meet deadlines, come to class prepared, and actually enjoy their classes. They are the average college professor’s dream come true!

They tend to become lifelong learners, creative and energetic employees, and quite often entrepreneurs. Most Montessori students grow up to be people of character; people you can trust and on whom you can depend. ey have warmth, humanity, and compassion with lives that reflect both joy and dignity. These are the men and women we hope our children will grow up to be.